Komparu School

The following is a brief introduction of KOMPARU-RYU (Komparu School),

the Noh school which is said to have the longest history among all schools

of Nohgaku <the generic name for Noh and kyogen combined>,

a traditional Japanese performing art.

With its accomplished sophisticated style, Nohgaku soars above others as

the pinnacle of classical performance arts of Japan. We welcome you to the

world of “Noh”, the oldest form of a musical on earth that lures you to a

realm of spellbinding fusion of utai <chant and chorus>, hayashi <music>

and mai <dance>.

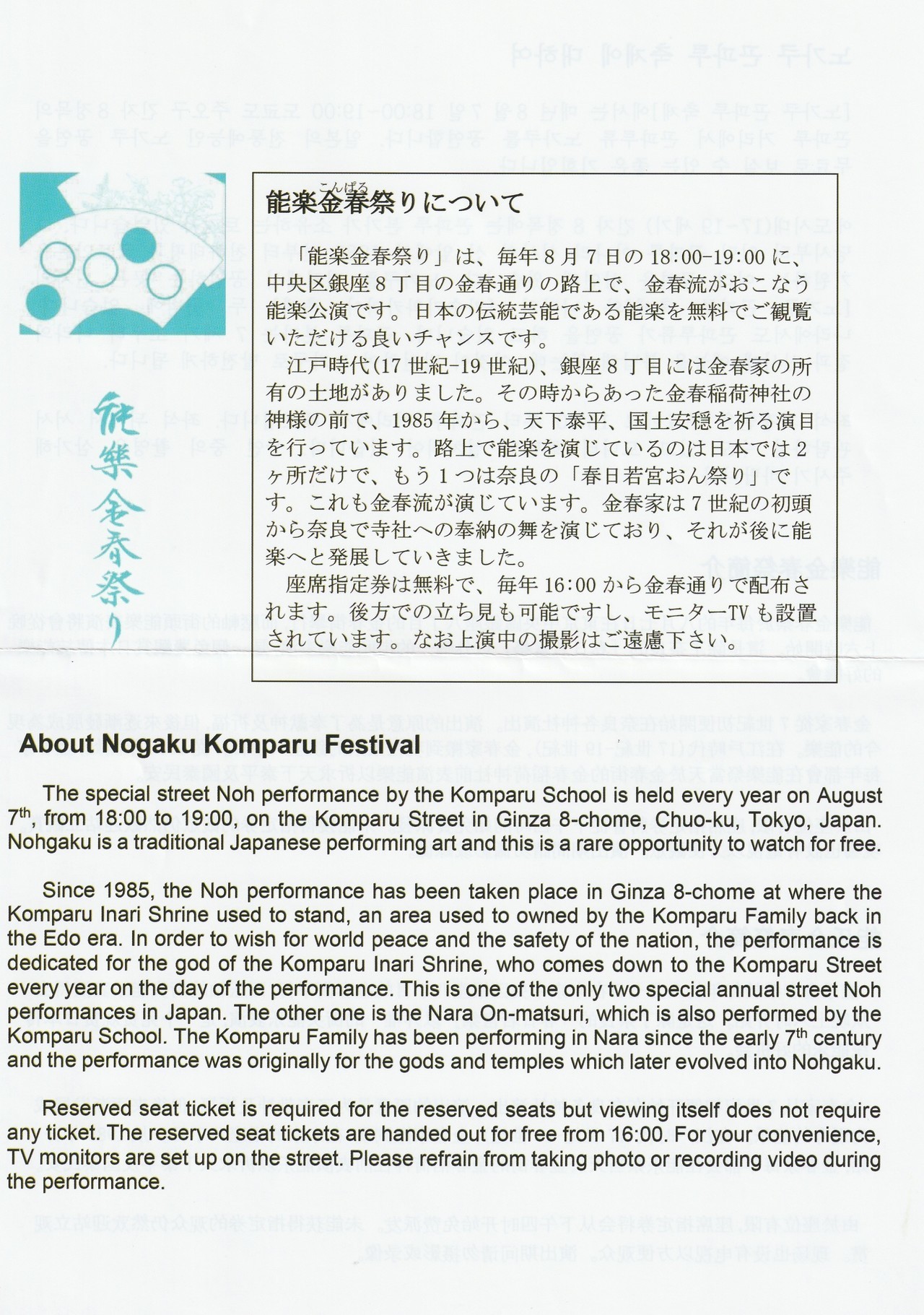

August 7th, from 18:00 to 19:00 Nogaku Komparu Festival

The special street Noh perfomance by th Komparu School is held on August 7th, from 18:00 to 19:00, on the Komparu Street in Ginza 8-chome.

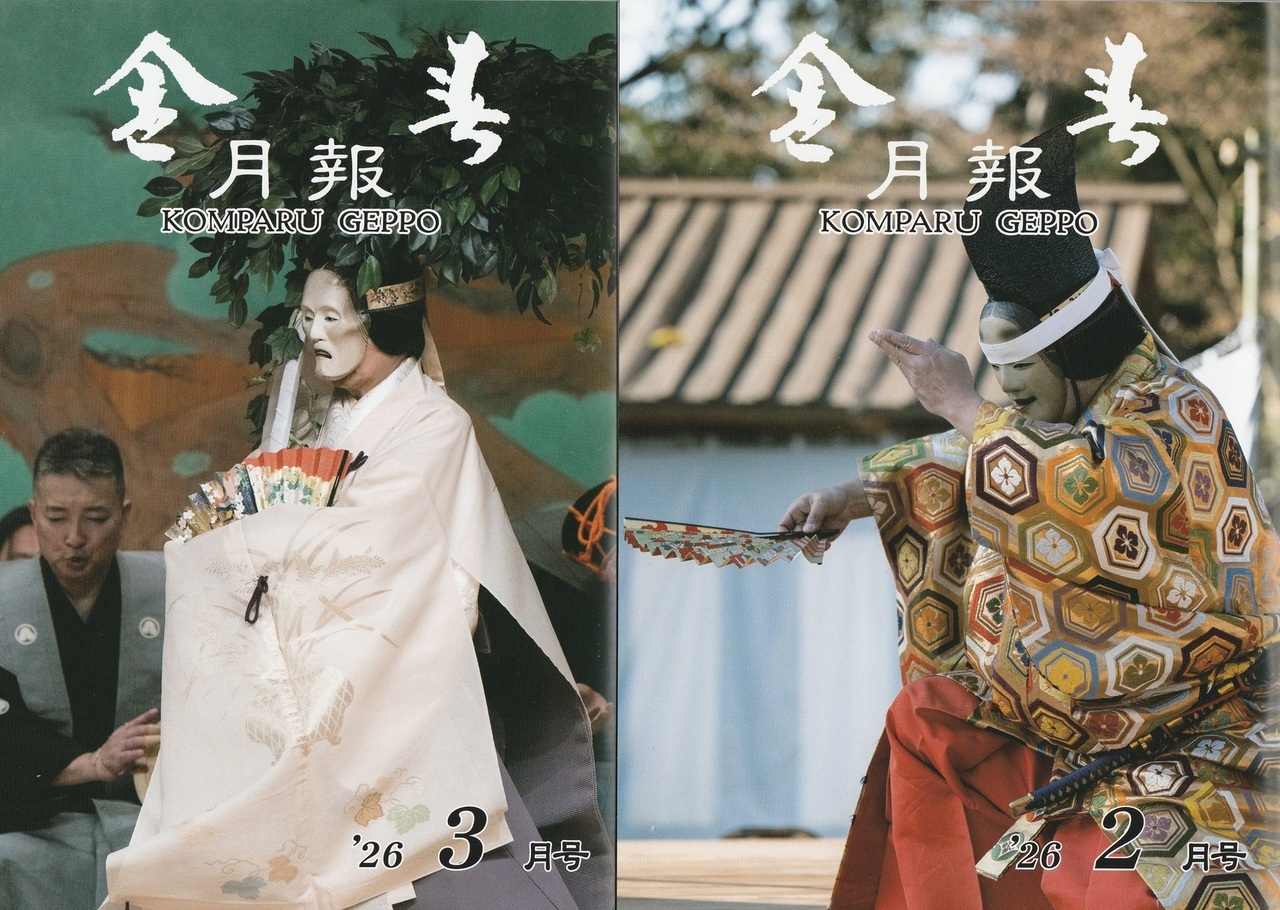

Experiencing Komparu School Noh performances

When and Where to See Noh Perfomances

of Komparu School

Information on the Komparu School Noh performances scheduled

in the coming months:

■September 10, 2023(Sunday)

Regular Noh Performance by Komparu School

Doors open at 11:45; Performance starts at 12:30;

You can buy tickets on the day. General Seating will be open seating.

Performance scheduled to finish at 17:20.

Three Noh plays: “Ebira” “Seiganji” “Ikkaku-Sennin”

At the National Noh Theater in Sendagaya, Tokyo

■September 10, 2017(Sunday)

Regular Noh Performance by Komparu School

Doors open at 11:40; Performance starts at 12:30;

Performance scheduled to finish at 17:00.

Three Noh plays: “Kasugaryujin,“Izutsu”and“Akogi”

At the National Noh Theater in Sendagaya, Tokyo

What is Komparu School?

The words passed down through hereditary succession has it that Komparu

School was founded around 600 AD by Hadano Koukatsu (the 1st generation),

who served Prince Shotoku, with the current iemoto <head of school>

Komparu Yasuaki being the 80th generation of the School. As such, Komparu

School is an unbroken lineage with the longest history among all schools of

Nohgaku. It is also the oldest school in terms of artistic style: Komparu

School is known to retain a wealth of time-honored formulaic styles, in both

utai <chant and chorus> and kata <movement patterns>. We hope you will

enjoy the simple yet sublime style of Komparu Noh.

Enjoying a Noh Performance

Although Noh has been incorporated into the UNESCO Representative List

of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, quite a few modern-day

Japanese people still tend to have the following perception of Noh as a

traditional Japanese performance art: “a bit low in action”; “difficult to pick

up the lines spoken”; “hard to know where the highlight of the drama lies”.

They also feel that “you need to have prior knowledge of all the set rules

in order to really appreciate Noh.” Admittedly, Noh comes with a lot of

conventions and rules. However, it is only the performers who are required

to stick to such conventions; in no way are these rules designed to facilitate

the audience’s understanding of Noh. To concentrate on what is taking place

onstage, irrespective of whether you “get it” or not, is probably the

recommended style of appreciating a Noh performance. Keeping your eyes

glued on the movements on the stage and straining your ears to the music

and the chant—while maintaining an open mind—is a shortcut to familiarizing

yourself to Noh. In other words, allowing oneself to be totally “absorbed” in

the dance movements and vibrant sounds of the music and the chant, and

finding “beauty” in the atmosphere created by the fusion of those elements,

is the key to enjoying Noh.

What Is Noh?

Noh is a form of theater. Often referred to as “music-and-dance

play” or “masque”, a Noh performance differs greatly from other

forms of theatric art in which the story unfolds mainly through

spoken lines. In contrast, a Noh play reenacts the inner thoughts

and emotions of human beings through song and dance. The sound

elements of Noh consist of verse/prose (known as “utai” ) and a

Noh orchestra comprised of a transverse flute, a small hand drum,

a large hand drum, and a large drum played with a stick. The “dance”

element is the locomotion pattern of the Noh actors. The sound

and the dance elements combined are capable of expressing a

whole spectrum of human emotions including delight, sorrow,

anger, resentment and hatred. Noh is also a theatrical art noted

for its frequent use of the mugen Noh (fantasy or dream Noh)

formula, in which the soul of a departed character enters the

dream of a living person to tell his or her story. A Noh play goes

well beyond simply reenacting the present reality; its mission is

to create a realm of a totally different dimension.

Above all, Noh is noted for its long and uninterrupted history

spanning many centuries. The art of Noh was perfected more

than 650 years ago, and the plays have been performed thereafter

without any period of lapse. This continuity has enabled Noh

plays to encapsulate the vivid sensitivity of people who inhabited

medieval Japan roughly around 1300 A.D. Being exposed to a Noh

performance allows us to tentatively entertain ourselves in a world

which is a complete departure from our day-to-day routine. The

polished verse and prose of medieval Japan; the rich emotions

highlighted by song-and-dance; the eloquence of the seemingly

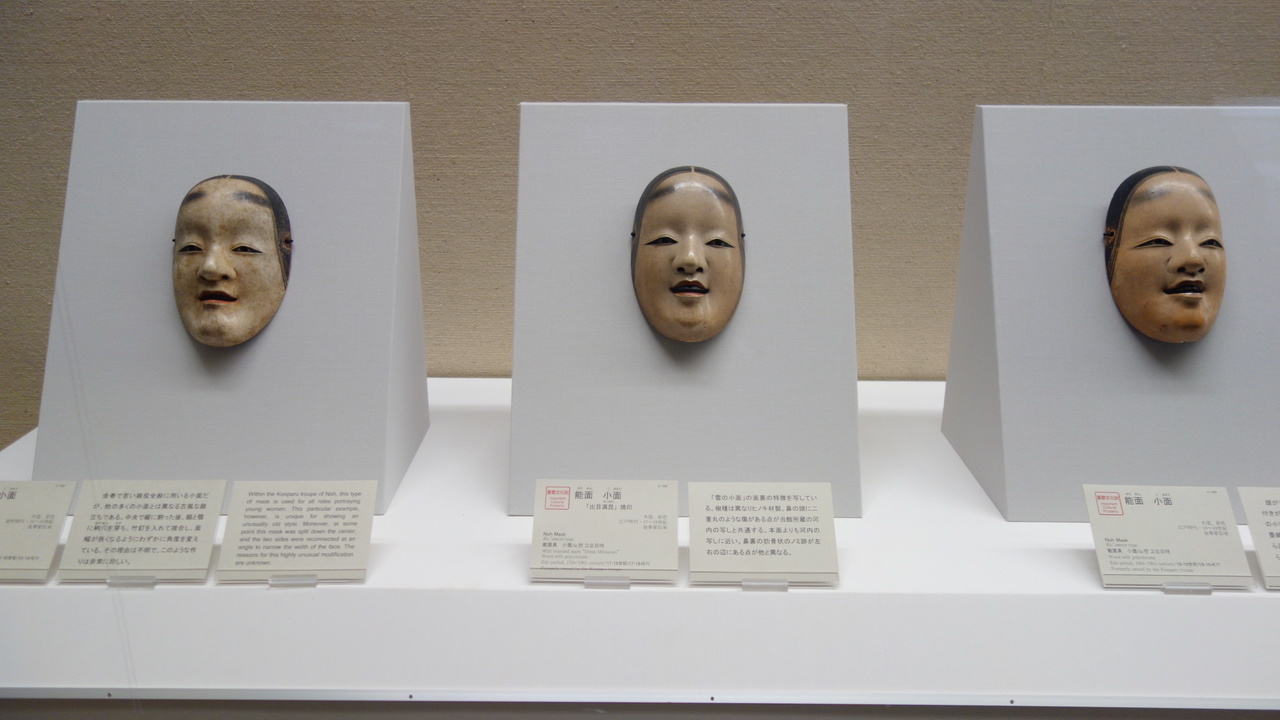

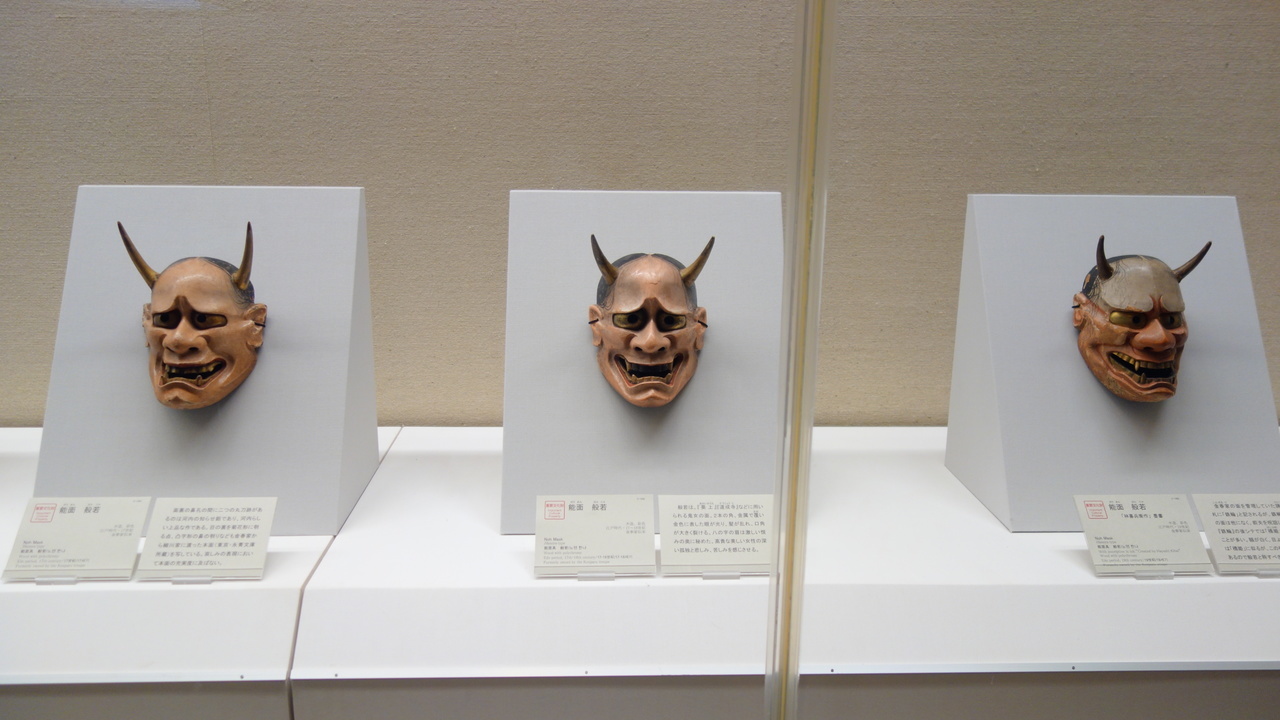

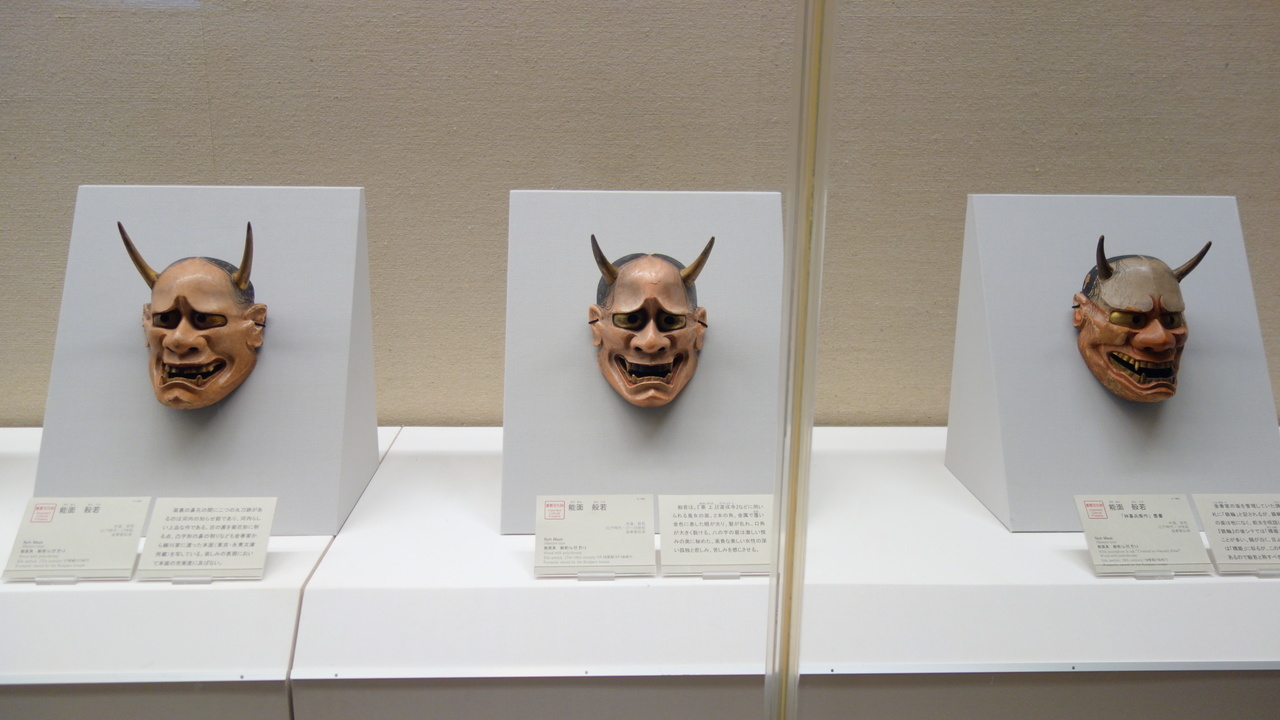

“impassive” Noh masks; the piousness of people in those days

and their customs…there is so much we can learn from Noh.

Noh is built on a “less-is-more” approach. Throughout its 650-year

history, Noh has consistently trimmed away “frills” – whether in

masks, locomotion patterns or stage props – to arrive at Noh as

we know today. Just as a Noh mask which seemed to lack facial

expressions comes alive during a Noh performance, the slightest

movement can play infinite functions on stage. Noh is a form of

art that has acquired the ability to symbolize anything and

everything through “omission”. Moreover, every motion in a Noh

play can be broken down into units of “kata” <movement

patterns>. These “kata”, which count about 250 in total including

idiosyncratic ones, are highly simplified and abstract in style.

The Noh Stage

Roofed but located indoors, a Noh stage is surrounded by an

area covered with white pebbles—a vestige from an earlier time

when Noh used to be performed in open fields. It was only since

the Meiji period (1868 –) that a Noh theater building, with a Noh

stage completely fitted inside, came to be constructed. As a rule,

a Noh stage comprises a square of approximately six meters on

each side, with a column on each of the four corners. These

columns help the performers, whose field of vision is extremely

curtailed with the wearing of a mask, confirm their positions while

they are on stage. An aged pine tree known as “oimatsu” is painted

on a back panel placed at a position directly facing the audience

seats, while three small pine trees are planted along the bridge

extending on the left side of the stage. These props serve to retain

the atmosphere of an era when Noh was an outdoor performance.

All natural scenery is symbolized through this single factor of a

pine tree, which is an evergreen whose leaves remain verdant

throughout the year.

Attending a Noh Performance

What sets Noh markedly apart from other forms of theatrical

art is that, Noh is not a one-way experience in which only the

spectator is profoundly moved by the performance: The audience

is required to have the right frame of mind to not only immerse

themselves in the voice, music and movements that are being

performed but also to try to understand, and accept, the

atmosphere created by the fusion of all these elements.

On the other hand, there is another – and a more ingenious –

way of appreciating Noh, which is to enjoy Noh while dozing off!

Occasionally, during lapses from peaceful slumber, you turn your

eyes onto the stage and find yourself gazing at a “celestial

maiden standing there”; or “a woman living in the wilderness,

crouching over a spinning wheel in her tumbledown shack,

spinning threads of an endless cycle of reincarnation”; or “a woman

in male attire, elegantly flapping her kimono sleeves in a dance of

reminiscence of a love in bygone days”…. This is indeed a slumber

of the highest class.

The Mysteries of Noh

Noh is a form of art in which only “one (a small part) out of

ten (the whole)” is expressly demonstrated. During a Noh

performance, you come up with one question after another:

Why does everyone consistently wear only “shiro-tabi”

<Japanese white socks> onstage? ; Isn’t it strange to see

a man’s jowl peeking under a mask of a beautiful woman? ;

Kyogen performers always sit with their feet tucked underneath

themselves. Why do Noh actors sit with one knee raised?;

When did they decide on the 4-instrument composition of

the Noh orchestra?; Why is it that three out of the four musical

instruments are percussions, while the flute is also played

mainly as a rhythmic instrument?; Why isn’t the flute played to

harmonize with the tune of the utai?; Wasn’t copyright an issue

when the Noh plays created by Zeami of the Kanze troupe were

incorporated into the repertoires of other troupes? ..... Welcome

to the mysterious world of Noh! One of the joys of Noh is that

you find yourself sharpening all your senses to be perceptive

enough to “understand the whole from only one small part”;

in other words, you are launching yourself on a journey to solve

the mysteries of Noh.

Roles in a Noh Play

The Actors

Shite-kata

Shite-kata is a lineage of male actors who play the main

character (protagonist) in a Noh play. Given the privilege of

wearing Noh masks onstage, they portray roles ranging from

men, women, old men and gods to oni <ogres>, tengu <long-nosed

goblins> and spirits of the departed. Shite-kata also provides

the Noh chorus known as jiutai, and is responsible for putting

together simple stage props. A Noh play is subdivided into two

parts, with the same actor playing the protagonists of both the

former and the latter parts, known as “mae-shite” and “nochi-jite”,

respectively. The secondary character co-acting with the shite is

called “tsure”. There are five schools of shite-kata including

Komparu School.

Waki-kata

Waki-kata is a role in a Noh play that consistently

represents a living male person. It is, in a sense,

a role that embodies the real world.

Kyogen-kata

Kyogen-kata are professionals who perform kyogen programs.

The main actor and supporting actor are called “shite” and “ado”,

respectively. Programs in which a kyogen actor performs a role in

a Noh play are referred to as “ai kyogen”, and those actors typically

portray characters who are even more real-world than the “waki”.

There are two schools of kyogen-kata: Okura and Izumi.

Hayashi-kata

Hayashi-kata is a generic term for the players of musical instruments

in Noh. Each performer exclusively plays one instrument, and never

an instrument other than his category. For each category of musical

instrument, there is more than one school.

The History of Noh

The World's Oldest Musical

Noh is believed to have been perfected in the Ashikaga

(Muromachi) period, more than six centuries ago, by Kan’ami

and his son Zeami. Up till that time, singing-only or lively

acrobatic acts presumably comprised the mainstream of

performance art in Japan. The credit goes to Kan’ami and

Zeami for picking out the “cream of the crop” of those arts

and incorporating them into a theatrical play driven by storylines,

in what may be called the world’s oldest “musical”. The verse

and prose performed in a Noh play today are almost identical to

those that were penned by Kan’ami and Zeami in their days.

It was in the year 1374 (or 1375) that the 3rd generation shogun

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu of Muromachi bakufu <feudal government>

had his first encounter with Noh at Imagumano shrine. Yoshimitsu’s

patronage and backing of Noh served as the key impetus for Noh

making a quantum leap forward. Incidentally, the English playwright

giant William Shakespeare was creating a sensation around the year

1600, which means that the musical theater genre in Japan was

already perfected 250 years before Shakespeare’s time.

Noh and Daimyo <feudal lords>

There is a reason why Noh managed to more or less retain its

original form while being passed down through centuries to the

present: The unstinting support from the power holders of each

era, namely the daimyo, had made this possible. It all started with

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the 3rd generation shogun of the Muromachi

feudal government, famous for commissioning the erection of

Kinkakuji (The Golden Pavilion), who was totally captivated by

the art of Kan’ami and Zeami. Subsequent feudal lords continued

to patronize Noh. In particular, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a passionate

supporter of Noh, to the extent that in the 1590s he had his heroic

episodes dramatized into a Noh play, starring himself as the protagonist.

Hideyoshi also merged and closed down various Noh troupes throughout

Japan, slimming down the number to the four troupes based in Yamato

(Nara prefecture). These four troupes are the origins of the present-day

four schools of Noh (Kanze, Komparu, Hojo and Kongo). (The Kita School,

on the other hand, was founded by command of Tokugawa Hidetada,

the 2nd generation shogun of Edo period). By the time Tokugawa Ieyasu

came into power, the status of Noh had been further elevated to become

the official shikigaku (ceremonial music) of the shogun government.

Meiji Period (1869 – ) onward

The collapse of the daimyo (feudal lord) regime of Edo period brought

about much social chaos and distress. Meanwhile, the lifting of Japan’s

self-imposed isolation triggered an influx of foreign culture which, in

turn, led to the re-appreciation of traditional Japanese culture. One of

the central figures who pushed Noh toward its longstanding popularity

was Iwakura Tomomi, who renamed Noh as “Nohgaku” and introduced

it to the world as Japan’s proud tradition.

The incorporation of Noh into the 1st “List of the Intangible Cultural

Heritage of Humanity”, announced by UNESCO in 2001, has given

Noh another reason for attracting world-wide attention.

The History of Komparu School

Komparu Zenchiku, the 57th head of Komparu School nicknamed

“the restorer”, was the son-in-law of Zeami, the perfector of

Nohgaku. His close ties with Zeami (the 2nd generation Kanze

Dayuu) is evidenced by the fact that he personally inherited from

Zeami, through hereditary succession, such esoteric texts as “Rikugi”

and “Shugyoku Tokka”. Under the tutelage of his father-in-law Zeami,

Zenchiku followed in his footsteps and further advanced the

formidable achievement made by Zeami in driving Noh toward its

perfected form. Among Zenchiku’s own accomplishments are such

masterpiece Noh plays as “Basho” and “Nonomiya” and a long list

of esoteric books including “Rokurin Ichironoki” and “Meishukushu”.

Going down the lineage from Zenchiku, Komparu School continued

to turn out a number of outstanding figures, including the 59th head

of school Komparu Zenpou. Worthy of special mention among them

is the 62nd generation head of school Komparu Yasuteru, whose

artistic style flourished under the protection and aegis of Toyotomi

Hideyoshi. After Tokugawa Ieyasu took over as the ruling shogun,

Yasuteru continued to be treated with special respect as the eldest

dayuu <prominent Noh actor> of the four troupes (Kanze, Hosho,

Komparu and Kongo), which further reinforced the important position

held by Komparu School in the history of Noh. Ranked second to Kanze

troupe in hierarchy, Komparu School in Edo period nevertheless had

under its command many influential branch families – Komparu

Hachizaemon, Takeda Gombei and Okura Dayuu, to name a few.

Today, the prestigious Sakurama family is one of the branch families

who are carrying on the refined style of Komparu School Noh.

Tokyo, Nara, Nagoya, Kumamoto, Fukuoka and Kagoshima are the

main present-day hubs of activity for Komparu School.

The current iemoto, the 81th generation Komparu Norikazu,

heads a public-interest incorporate association called

Komparu-Enmaikai, named after the Enmaikai troupe which

was one of the four enormously successful troupes of sarugaku

<prototype of a Noh play> of Yamato in mid-14th century.

Although Hadano Koukatsu is said to be the founder of Komparu

School, the first person to actually use Komparu as a surname

was Komparu Gonnokami who was the 53rd generation down

the lineage. Gonnokami did not inherit the school as head, but

his son Yasaburo was picked out as the 56th head of Komparu

School, and his line of descent continues to the present day.